16.04.2025

Denica Perková is a newly graduated art theorist who did an internship with the Living Art Museum from mid-February to mid-May and assisted with the installation and the overseeing of the collection exhibition New Acquisitions: Received, Remade, Replaced. One of the works caught Denica's attention, Puffin Shop by Hulda Rós Guðnadóttir. The following is a written piece by Denica on the piece:

From March 15 to April 27, 2025, The Living Art Museum hosted the exhibition New Acquisitions: Received, Remade, Replaced, curated and managed by the collection manager Jenny Barrett. The exhibition offered a rare glimpse into the workings of the museum’s archive, highlighting the challenges associated with the maintenance, repair, and even potential theft of artworks. Among the pieces on display, one in particular attention — Puffin Shop.

The work, created by Icelandic artist Hulda Rós Guðnadóttir, was first exhibited in 2019 as part of the expansive multimedia installation All is Full of Love at Künstlerhaus Bethanien in Berlin. Today, the piece feels increasingly relevant, acquiring a near-prophetic resonance.

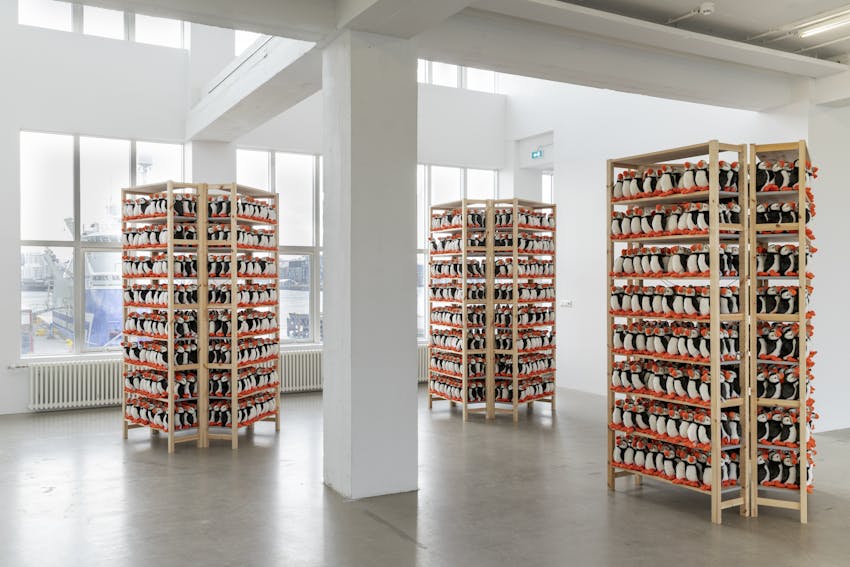

The installation features three triangular arrangements of IKEA shelves placed at precise angles, each meticulously filled with a total of 2,470 plush puffins. The design deliberately evokes the visual language of souvenir shop displays. The triangular formations symbolize the three fundamental pillars of the Icelandic economy: fishing, tourism, and the arts. At the center of the installation is the puffin — once a common seabird inhabiting the North Atlantic cliffs, now transformed into a ubiquitous emblem of Iceland, found on keychains, T-shirts, and as plush toys flooding Reykjavík's tourist areas.

The puffin first appeared in Hulda Rós's work in 2006, four years before images of the Eyjafjallajökull volcanic eruption spread globally, fueling fascination with Icelandic nature and a surge in tourism. Throughout her practice, the puffin reemerges, though its significance evolves notably. In her 2006 performance project Artist as a Puffin, the artist — dressed in a puffin costume — playfully and ironically explored themes of cultural identity and the early stages of Iceland's stereotypization. By contrast, the 2014 piece Material Puffin adopted a more somber tone, depicting a puffin wandering through harbors increasingly stripped of their character through commercialization. Here, the puffin gradually becomes a stranger in the very landscape it symbolizes.

In Puffin Shop, however, the transformation is complete. The puffin is no longer a figure or a performative tool; it is reduced to a mere object, mass-produced in China.

The installation is accompanied by a rhythmically shifting sound composition by Joseph Marzolla. The soundscape draws from deconstructed texts by Hulda Rós, recordings of puffin calls, and choral singing by an Icelandic choir based in Berlin. Though initially unobtrusive, the soundtrack’s persistent repetition evokes the atmosphere of so-called "elevator music," typically heard in public and commercial spaces. Here, however, sound serves not as background, but as a critical layer of meaning. The audio component restores a "voice" to the plush puffins, while simultaneously posing a provocative question: are visitors — and by extension tourists — even aware of what a real puffin sounds like, or have they forgotten that it is a living creature?

Puffin Shop raises profound questions about value and authenticity. The puffin — once a vibrant, living being — has been reduced to a simulacrum, a copy of a copy devoid of real connection to the Icelandic environment. Its production, outsourced abroad, underscores the irony that even in Iceland, souvenirs are rarely locally made. What remains genuinely Icelandic about the puffin, and what does Icelandic identity itself mean when it becomes part of the machinery of commercialization?

Within the context of New Acquisitions: Received, Remade, Replaced, the installation acquires an additional dimension. The puffin here is not only a symbol of cultural appropriation or kitsch; it is a sign of disappearance. In recent years, puffins have increasingly been associated with ecological threat, as their populations have plummeted due to climate change and human activities. The tourism industry that once helped popularize the puffin now contributes to its decline. The irony is stark. And deeply unsettling.

How many puffins must there be before we stop noticing what they once truly meant?

The photograph following the article is taken of Hulda Rós's piece Puffin Shop in New Acquisitions: Received, Remade, Replaced by Sisters Lumieré.

Denica Perková is a newly graduated art theorist who did an internship with the Living Art Museum from mid-February to mid-May and assisted with the installation and the overseeing of the collection exhibition New Acquisitions: Received, Remade, Replaced. One of the works caught Denica's attention, Puffin Shop by Hulda Rós Guðnadóttir. The following is a written piece by Denica on the piece:

From March 15 to April 27, 2025, The Living Art Museum hosted the exhibition New Acquisitions: Received, Remade, Replaced, curated and managed by the collection manager Jenny Barrett. The exhibition offered a rare glimpse into the workings of the museum’s archive, highlighting the challenges associated with the maintenance, repair, and even potential theft of artworks. Among the pieces on display, one in particular attention — Puffin Shop.

The work, created by Icelandic artist Hulda Rós Guðnadóttir, was first exhibited in 2019 as part of the expansive multimedia installation All is Full of Love at Künstlerhaus Bethanien in Berlin. Today, the piece feels increasingly relevant, acquiring a near-prophetic resonance.

The installation features three triangular arrangements of IKEA shelves placed at precise angles, each meticulously filled with a total of 2,470 plush puffins. The design deliberately evokes the visual language of souvenir shop displays. The triangular formations symbolize the three fundamental pillars of the Icelandic economy: fishing, tourism, and the arts. At the center of the installation is the puffin — once a common seabird inhabiting the North Atlantic cliffs, now transformed into a ubiquitous emblem of Iceland, found on keychains, T-shirts, and as plush toys flooding Reykjavík's tourist areas.

The puffin first appeared in Hulda Rós's work in 2006, four years before images of the Eyjafjallajökull volcanic eruption spread globally, fueling fascination with Icelandic nature and a surge in tourism. Throughout her practice, the puffin reemerges, though its significance evolves notably. In her 2006 performance project Artist as a Puffin, the artist — dressed in a puffin costume — playfully and ironically explored themes of cultural identity and the early stages of Iceland's stereotypization. By contrast, the 2014 piece Material Puffin adopted a more somber tone, depicting a puffin wandering through harbors increasingly stripped of their character through commercialization. Here, the puffin gradually becomes a stranger in the very landscape it symbolizes.

In Puffin Shop, however, the transformation is complete. The puffin is no longer a figure or a performative tool; it is reduced to a mere object, mass-produced in China.

The installation is accompanied by a rhythmically shifting sound composition by Joseph Marzolla. The soundscape draws from deconstructed texts by Hulda Rós, recordings of puffin calls, and choral singing by an Icelandic choir based in Berlin. Though initially unobtrusive, the soundtrack’s persistent repetition evokes the atmosphere of so-called "elevator music," typically heard in public and commercial spaces. Here, however, sound serves not as background, but as a critical layer of meaning. The audio component restores a "voice" to the plush puffins, while simultaneously posing a provocative question: are visitors — and by extension tourists — even aware of what a real puffin sounds like, or have they forgotten that it is a living creature?

Puffin Shop raises profound questions about value and authenticity. The puffin — once a vibrant, living being — has been reduced to a simulacrum, a copy of a copy devoid of real connection to the Icelandic environment. Its production, outsourced abroad, underscores the irony that even in Iceland, souvenirs are rarely locally made. What remains genuinely Icelandic about the puffin, and what does Icelandic identity itself mean when it becomes part of the machinery of commercialization?

Within the context of New Acquisitions: Received, Remade, Replaced, the installation acquires an additional dimension. The puffin here is not only a symbol of cultural appropriation or kitsch; it is a sign of disappearance. In recent years, puffins have increasingly been associated with ecological threat, as their populations have plummeted due to climate change and human activities. The tourism industry that once helped popularize the puffin now contributes to its decline. The irony is stark. And deeply unsettling.

How many puffins must there be before we stop noticing what they once truly meant?

The photograph following the article is taken of Hulda Rós's piece Puffin Shop in New Acquisitions: Received, Remade, Replaced by Sisters Lumieré.